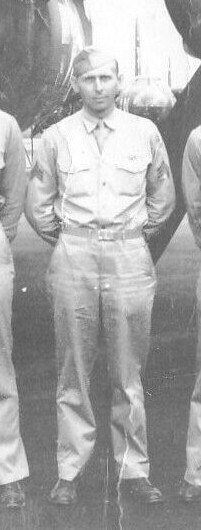

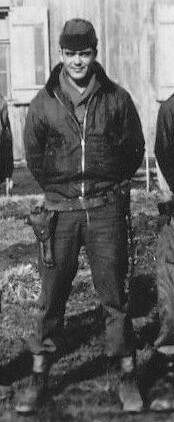

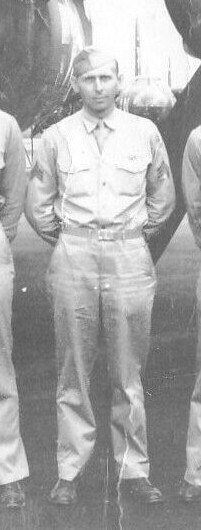

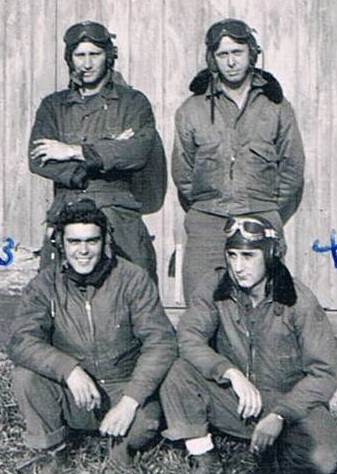

Sgt Howard Noelting |  Sgt James Ray |  Sgt Macklynn Worsham |

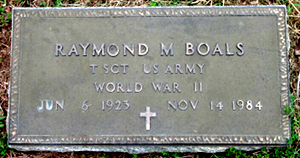

Sgt Raymond Boals |

Sgt Howard Noelting |  Sgt James Ray |  Sgt Macklynn Worsham |

Sgt Raymond Boals |

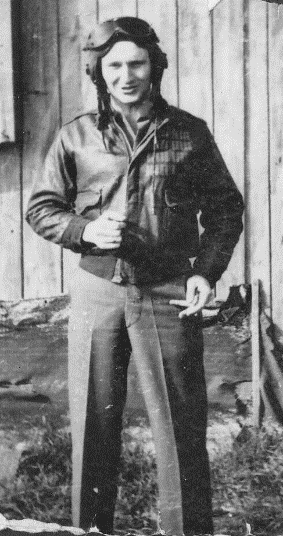

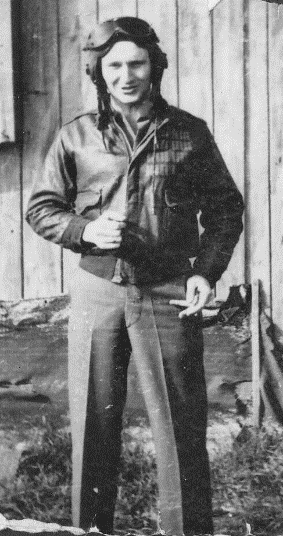

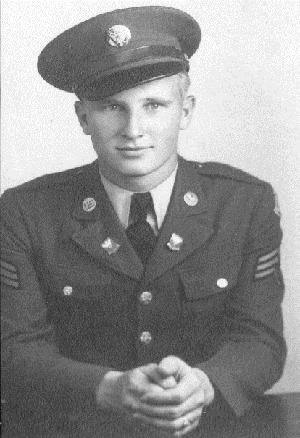

| Sgt. James Ray | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sgt. Harold Noelting |

|---|

|

|

|

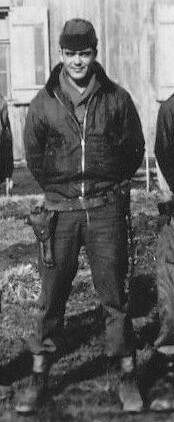

| Standing : Noelting and Worsham Kneeling : Boals and Hopping |

September 21, 1944 (actual crash photo) |

|

|

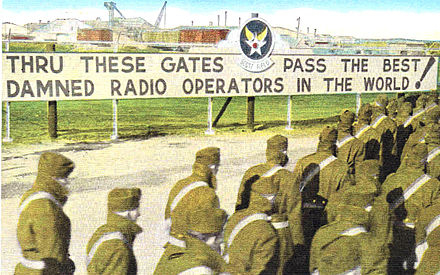

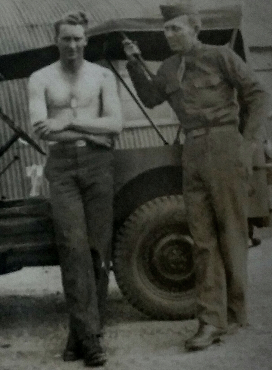

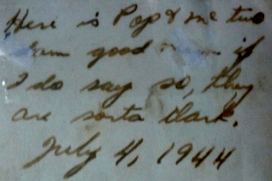

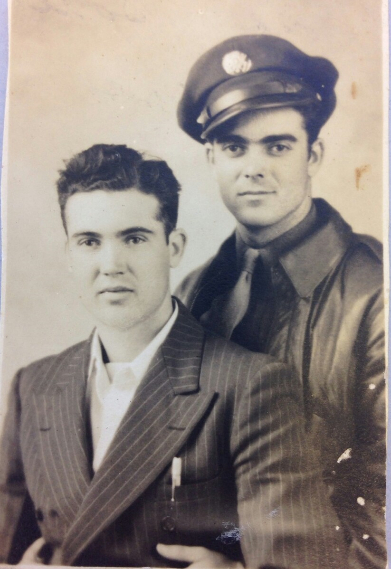

Clinton and Raymond, 1943 |

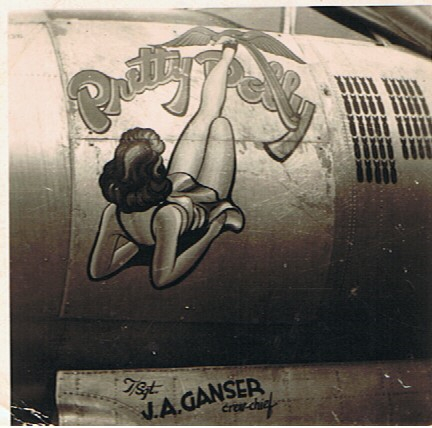

Ship 42-96226, “Pretty Polly” |

|

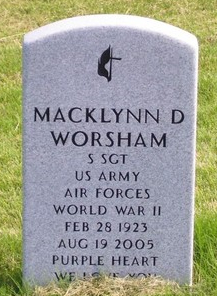

Harold L. Noelting - KIA - 21 SEPT 1944 |

|

|

|

|

|

|