THE PEAVINE RAILROAD

The Camp

A little village or camp for the Peavine employees sprang up in the quiet wilderness surrounded by oak, Chestnut, Popular, Hemlock, Maple and other tree species, at the foot of the mountains in close vicinity of the logging operations so the employees could walk to work. In the green forest deer, bears, turkey buzzards, wild cats including Links and Bob-cats and Black Panthers, wild turkey and other wild animals roamed freely. The animals and the Peaviners co-existed well there, sharing water and habitat as well. Many buildings scattered near the camp formed the little village.

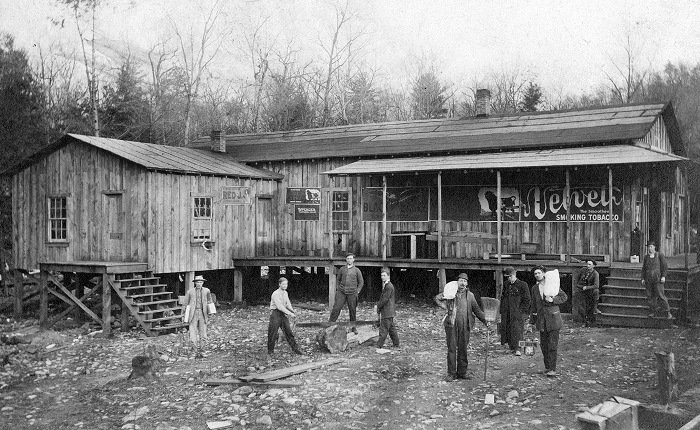

Logger and skidder crews of the John Heilman Lumber Co. pose in front of their lumber camp located at the base of the mountain. Circa 1911

The Camp Commissary

The commissary was the center of the camp's activity with shoppers coming and going all during the day. Mrs Pearl Reaves Laws (m. Charlie Laws), commissary clerk and daughter of Cal Reaves (w. Flora Belle "Florie" McCoy), the blackmsith, assisted them. School children sometimes stopped in on their way to school to buy a pencil, the men of the camp went to the commissary for tobacco during their dinner break and after work for other supplies and ladies stopped for thread and sewing things and to check the post office which was located in the commissary for letters and post cards. The Greystone Post office opened July 1, 1902 and closed November 15, 1919. It is believed by the author, that the Greystone post office was located at the Peavine camp.

The commissary building was a large one story, vertical weathered board structure, raised about three or four feet off the ground on wooden stilts with a covered porch. It set very close to the housing section. The front of the building had a Velvet Smoking Tobacco tin sigh complete with large bull and a couple of other smaller tin product advertisement signs nailed to the boards. The Peavine tracks had been laid to the side opposite of the office addition.

At the Commissary the employees could buy soap, brooms, kerosene, matches, Velvet brand smoking tobacco and pipes for smoking, candy, school supplies such as pencils and tablets, fabric, thread, buttons, bib overalls, socks, shoe laces, and dry goods, canned food items such as dried beans and salt pork, flour, corn meal, fresh produce, hardware and other necessaries for the logger and his family. The loggers could charge such items against their wages by using a line of credit called a "scrip", sometimes called a dugaloo or doogaloo. The charges were taken directly out of the workers pay checks.

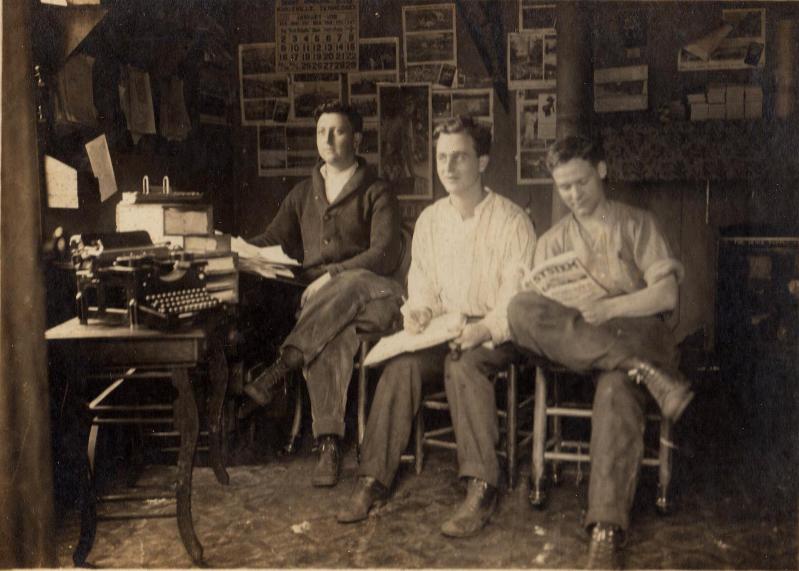

The store's inside looked similar to the one in the following picture:

Inside White Lumber Company Commissary near Elk Park, NC (ca 1911)

Photograph contributed by Marty Masker.

Several other buildings were included in the camp all encircled by the brushy green embrace of the forest. Among them was the main boarding house or bunk house which was a two story, wooden structure with many rooms. The lower floor had a covered porch with a some-what long, wooden ramp leading to it, directly from the train tracks. The ramp was built up off the ground to protect the workers from mud and water.

It is believed that the camp grub hall was located on the first floor of the boarding house. First cut wood from the camps saw mills had been thrown from the train and was kept piled up in front of the house to be used as heating fuel and keeping the cook stoves running.

The main boarding house at the John Heilman Lumber Camp. Tracks of the Greeneville & Nolichuckey Railroad are in the foreground. Circa 1911

Lady on the left is Minnie Painter, waitress, age approximately 20yrs

Lady next to Minnie is Elizabeth Painter, housekeeper, age approximately 64yrs

The Peavine Boarding House

A cook, usually a man, and one or more assistants were employed by the camp. Ruth Harrison born 1895, mother of Joe Harrison, lived at home and worked in the kitchen before she was married. The cook spent long hours baking bread, cakes, fried pies and oven pies. The cooks helper sometimes called the cookee, peeled potatoes, swept, carried water and wood and washed the dishes.

A weekly order for food supplies was made by the cook and the boss would go to town, via the train for them. He brought back canned goods bought in gallon cans, large sections of salt pork, dozens of eggs and coffee by the pounds, flour in 196 pound barrels. The camp used 10 such barrels a week, among other things. Local farmers sold extra produce to the camp, fresh vegetables like beans, corn, tomatoes, watermelon, milk and butter, beef, sheep and pork.

At meal time, the men served themselves on tin plates and cups of all sorts set on the table. They could have whatever and as much as they wanted. The hard labor called for healthy appetites. If the men had plenty to eat, they would be more productive.

Breakfast was served at 5:30 am, which was eaten in the light of a kerosene lamp. A typical breakfast consisted of fried potatoes, eggs, different meats of ham steaks, sausage and bacon, with biscuits and coffee.

The men not living in the camp walked from home up to the cutting sites on the mountains. They got out of bed well before daylight, dressed, ate breakfast, then used their kerosene lanterns to light the way up the mountain. Once they reached their destination, they hung their lanterns in a tree to work by until daylight. They worked until dark and then used the lanterns again to get back down the mountain to home. The company usually furnished the noon meal at the cut site.

The noon and supper meal usually consisted of choices of salt pork and beef, and a variety of vegetables such as beans, potatoes, beets, corn, greens, cabbage, turnips and some times pea soup and stews and of course corn bread, biscuits, sourdough bread, cakes and pies and lots of coffee.

Men working up in the hills, farther away from the grub house at noon, had their food taken to them on carts. They sat on logs and held their tin plates in their laps.

Supper was eaten after the quitting time steam whistle was blown.

The bunk house was mostly for the single men who had left their wives and mothers back home. For about $3.15 per week, the men could have a warm bunk bed and three square meals a day. The camp grub house looked very much like the one in the picture below:

Photograph used by permission of Minnesota Historical Society. Photographer: William F. Roleff

Typically, bunk houses were not the cleanest places to live. Occasionally bed bugs and lice also found their way in, on not-so clean bodies. The men itched all over from the bites. Even with lice powders, there was not an effective way of ridding the place of them, kerosene was about the only cleaning method of the day, but the bugs always came back. When the men returned home to their wives and mothers the ladies burned their clothes hoping to keep the pesty bugs from infesting their homes.

The men had no bath houses. Washing from a tub, on a Saturday night was their only weekly bath. They usually only shaved one time a week, on Saturday night, also. Some chose not to bath or shave weekly.

An office which had been built onto the commissary, as an end addition took care of hiring and payroll and other important papers. The office had three windows and an outside door with steps going down off a small square ramp in the rear. There was a second door leading to the porch of the commissary for a partially covered walk in the rain to the company store door. The office was run by Mr. Bunah Basil Tullock born circa 1890. He was the bookkeeper, pay master and secretary. It was similar to the White Lumber Company office in Elk Park, NC shown in the following picture taken about 1911:

Noah Lewis, Lack Griffith, Clyde Ephraim Pearce

Photo contributed by Marty Masker.

The Camp Office Was Located In The Left Addition Of The Commissary, as seen in this Peavine picture.

The Heilman Lumber Company's commissary and main office (at left).

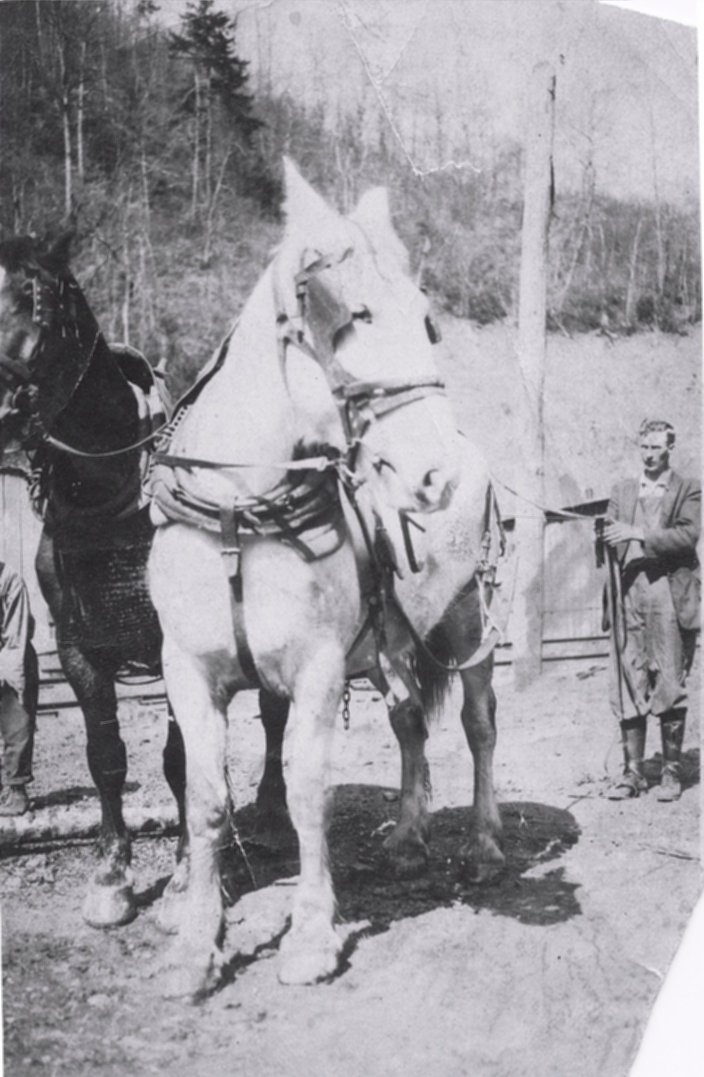

The camp had stables or barns for the mules and horses that supplied power in the logging camps. There was some horse barns located at the Old Forge Campground parking lot at Horse Creek Park and houses scattered up the creek were facilities associated with the Peavine operation also.

The operation used mostly mules which were cheaper to buy. But a few horses and oxen were also used.

The stable not only housed their food but gave the animals safe refuse at night from roaming wild cats and bears in the forest. The teamster foreman took great care of the livestock. No one wanted to lose a team under a pile of carelessly placed logs or to a wild animal. The teamsters typically only worked with the teams. They often had separate housing from the loggers, because they had to be up earlier in order to have the teams ready when the loggers needed them. The livestock was fed early and dressed in their gears for the day ahead. Teams of horses were matched for speed and weight.

According to Vesta Ona Reaves Ellis, daughter of Cal Reaves, blacksmith, the Peavine operation had two of the biggest horses that she had ever seen. One of the horses was named Ole Meg.

Team of horses as seen in this Peavine picture.

Jim Gunter holds the reins of a team of horses (Percheron breed) owned by Cal Reaves and leased to the railroad in this photo. One of them was called Ole Meg and the other was called Bird. Sharlene Gregg's great-grandfather, John Calvin 'Cal' Reaves, worked at the Peavine as the blacksmith when Hugh White owned the company. Sharlene's mother remembered Vesta (Sharlene's grandmother) talking about two horses, they were the largest horses that she had ever seen. Cal traded horses with Mr. Jim Holt in Greeneville on McKee Street. Holt Stables was next to the little brick warehouse. Mr. Holt married Cal's sister making them brothers-in-law. Cal broke logging horses that he got from Mr. Holt. One of his jobs as blacksmith was to make shoes and shoe nails for the horses. One shoe was hanging in the blacksmith shop. It was the biggest horseshoe that Mr. Reaves daughter, Vesta, had ever seen. Cal was a little man, he may very well be in the photo with the horses.

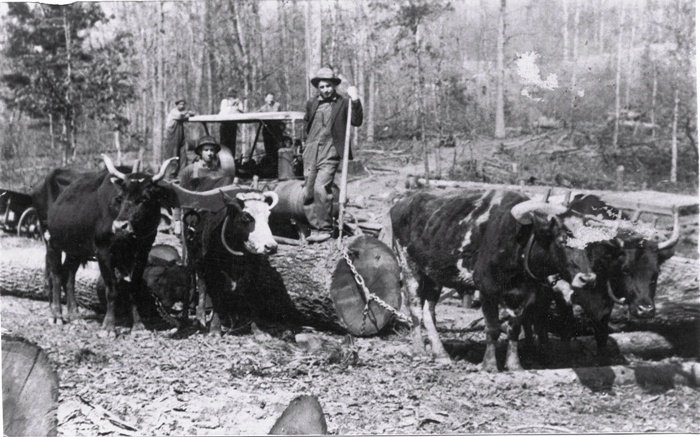

Thomas Philip Jennings running the steam engine that powered the portable sawmill.

Photo courtesy Bryan and Joyce Ramsey. Tom 'Papaw' Jennings is Bryan's grandfather.

Portable sawmill behind oxen team as seen in this Peavine picture.

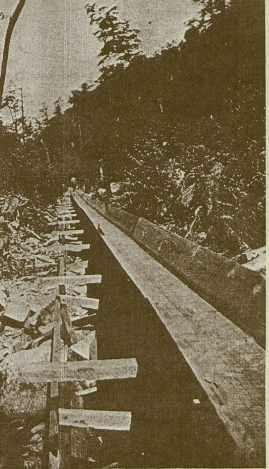

Two company water flumes were located in Phillips Hollow and Bullen Hollow. The flumes were used to transport lumber sawed from a portable sawmill in mountains down to the base of the mountain, via the water.The lumber floated down the flume right into the hands of men down below who stacked it on the spot until it could be picked up by the train.

Peavine Water Flume

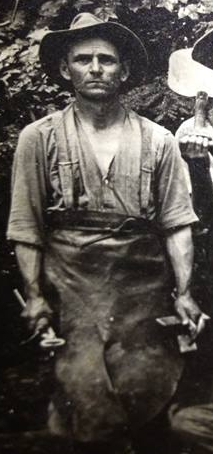

Also on sight was a blacksmith's shops for making repairs to the machinery and shoes for the live stock. The company employeed only one blacksmith, John Calvin 'Cal' Reaves. Much metal was heated and bent to keep the operation going. Cal would take an iron rod and form horseshoes and horseshoe nails. Two of the horses were especially large. Vesta Reaves, daughter of Cal, remembered seeing a horseshoe for one of them hanging in the shop and noted they it was the largest horseshoe that she had ever seen. One of the huge horses was called Ole Meg. The shop would have looked something like the picture below, which was taken in another camp.

Photograph used by permission of Minnesota Historical Society. Photographer: William F. Roleff |  Peavine Blacksmith - Lawrence Hallum Tools - Hoof Trimmer, Fuller Photo courtesy of Teresa Dunbar Johnson |

In a good, flat spot at the base of the mountains, several feet from the creek and spring, very near the commissary, the camp offered a housing area for the families.

The lumber jack, from outside the community, and his family were furnished set-off houses, some called them spring houses or shanties, brought in by the railroad and set off along the tracks. The early made, mobile homes which measured about 8x10 feet, sometimes painted red, were made of vertical, unplaned boards and offered no insulation from the cold winds. One entry door on the long side and small window on the opposite side were the only openings in the structure. The little tin roof peaked just enough to let the rain and snow slide off.

Pot belly and little square cast iron stoves were used for heating the home and cooking the food. The stove sat on the wooded board floor which rested on sturdy floor joists.

Two feet wide concrete walkways made with crushed field stone in the mix, divided the family area with set-off houses on both sides of the walk. It started at the edge of the tracks and went straight through, the whole length of the living area and stretched back to the spring. A step or two as needed, was placed outside of the buildings so the people could get in and out of their temporary homes easily. Furniture, such as feather and straw tick beds and a table and chairs for eating, were furnished by each family. Coal-oil (kerosene) lamps were used for lighting after dark. For larger families, extra houses were used as needed. Mother used the dining table to wash the dishes in large pans, prepare food, and iron the family's clothes. Wooden pegs mounted on the walls around the room held the Sunday clothes and an extra set of work clothes. Tin plates and cups were stacked on the table after washing. The cast iron skillet and stew pot were hung on the wall near the wood stove used for both heating and cooking. Eating utensils were dropped into a jar and stored on the table. Extra blankets and towels were kept in a family trunk, where the Family Bible was usually stored. Childrens' play things were kept under the bed. Children usually had things like a checker set, bean flips, pull toys, or rag dolls, all of which were usually homemade. Children used cigar boxes to store treasures like arrowheads and marbles, and sometimes doll clothes. Father's gun was hung over the bed.

Photo used by permission of Jim Thurston and Little River Railroad Museum in Townsend, TN

Mothers with children lived in the camps to be close to their husbands. They gave the camp a feeling of a real community.

Barefoot school-aged children, with lunch pails in hand, walked about 1 1/2 mile to Bethany, a two room school house, for learning reading, writing and arithmetic. Bethany, which also educated other children in the area, had been built by the Presbyterians. The schoolhouse was located in a cozy setting on a cleared spot in the mist of the forest on a good stone foundation. It offered education for grades 1-8.

Photo (ca 1914) courtesy of Terry Harrison

The school yard had a make-shift ball diamond out to the side, for recess fun and lunch time. After the lunches of various foods like boiled eggs, sausage, ham, tenderloin, tator and jelly biscuits, sweet potatoes, bacon sandwiches, apples and different pies fried and baked were eaten, and all had had a fresh dipper of cold water from the spring, the children could play. The teacher usually set on the steps watching the children and graded papers as they worked off their lunches. The boys joined in a game of base-ball and the girls jumped rope and placed field stone in rows to mark off rooms for their pretend play houses. When lunch time was over, the teacher rang her hand bell, calling the children indoors again. Across the wagon trail road from Bethany, a water tank for the steam boiler for the trains had been placed for easy access. Reminders of the logging company were every where in the community.